Immigrant Laborers From Haiti Are Paid With Abuse in The Dominican Republic

By GINGER THOMPSON

GUATAPANAL, Dominican Republic - The tobacco fields are being planted a little late this year because the Haitian immigrants who work them were driven away by threats of a lynching.

The troubles in this farm town in the country's northwest started in late September, with allegations that a Dominican worker had been killed by two black men. Too angry to wait for a trial, local Dominicans armed themselves with machetes and went out for vengeance.

The troubles in this farm town in the country's northwest started in late September, with allegations that a Dominican worker had been killed by two black men. Too angry to wait for a trial, local Dominicans armed themselves with machetes and went out for vengeance.

"Where there are two Haitians, kill one; where there are three Haitians, kill two," said leaders of the mobs that descended on the immigrants' camps, the Haitians here recalled. "But always let one go so that he can run back to his country and tell them what happened."

Several Haitian workers were beaten by the Dominican mobs, said Jacobo Martínez Jiménez, an immigrant organizer. One Haitian, Mr. Martínez said, drowned when he fell into a river as he tried to get away. At least half of the town's 2,000 Haitian workers fled, as they said they had been warned to do, back across the border to Haiti, which shares the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic. Hundreds of others hid in the hills to the east, hoping that Dominican tempers would cool so that they could return to their jobs.

The attacks on Haitians here provide the most recent example of what international human rights groups describe as the Dominican Republic's systematic abuse of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent. In recent years, those organizations report, tens of thousands of Haitians have been summarily expelled from the country by individuals and the government, forcing them to abandon loved ones, work and whatever money or possessions they might have.

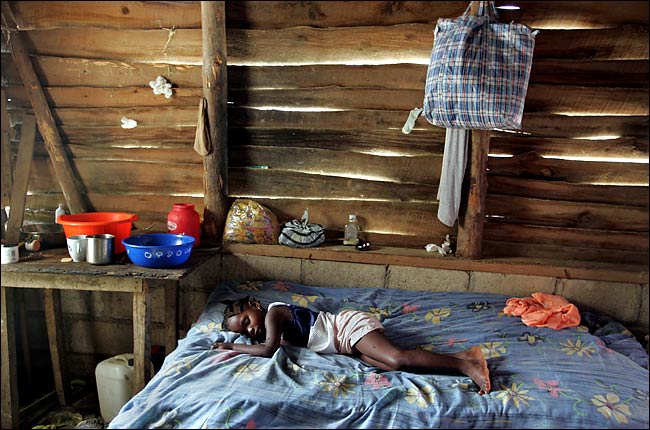

"We do all the work, but we have no rights," said Victor Beltran, one of about 150 Haitian immigrants, most of them barefoot and dressed in rags, who had taken refuge in a rickety old barn.

"We do all the work, but our children cannot go to school. We do all the work, but our women cannot go to the hospital. "We do all the work," he said, "but we have to stay hidden in the shadows."

Among those who have been deported, said Roxanna Altholz, a lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley, are Spanish-speaking Dominicans who were born to Haitian parents but have never visited Haiti, much less lived there.

At the root of the problem, Ms. Altholz said, is that Haitian immigrants and their Dominican-born children live in a state of "permanent illegality," unable to acquire documents that prove they have jobs or attend schools or even that they were born in this country. In October, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued an opinion that the Dominican Republic was illegally denying birth certificates to babies born here to Haitian parents, and ordered the government to end the practice. Human Rights Watch has also published extensive investigations of the mass expulsions, and the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child has expressed concerns about Haitian children being denied access to education and medical care.

"Snatched off the street, dragged from their homes, or picked up from their workplaces, 'Haitian-looking' people are rarely given a fair opportunity to challenge their expulsion during these wholesale sweeps," Human Rights Watch reported in 2002. "The arbitrary nature of such actions, which myriad international human rights bodies have condemned, is glaringly obvious."

Several Roman Catholic priests here have been threatened with legal action, including expulsion from the country, after the authorities found that they had illegally obtained birth certificates for dozens of Dominican-Haitian babies by falsely declaring them to be their own. One of the priests has also been receiving death threats, prompting the church to move him out of the country temporarily for his safety

"By keeping Haitians in a limbo of illegality, the government can do whatever they want with them," said the Rev. Regino Martínez Bretón of the Jesuit-run agency Solidaridad Fronteriza, in Dajabón, a city on the Dominican border. "The government can bring as many Haitians here as they want and then throw them away when they don't want them anymore."

Racism helps fuel the anti-immigrant sentiment, human rights groups say, since Haitians tend to have darker skin than Dominicans and are therefore often assumed to hold a lower social status.

The two countries have been volatile neighbors for most of the last two centuries, beginning with Haiti's domination of the Dominican Republic after its independence from Spain in the early 1800's. A century later, Rafael Trujillo, then the Dominican dictator, ordered the executions of some 37,000 Haitians in what many historians have called a ruthless campaign of ethnic cleansing. Indeed, the river that separates Haiti from the Dominican Republic is called Massacre River because of the slaughter.

Although anti-Haiti talk has since become a standard part of Dominican politics, the police and the military have made fortunes trafficking Haitians into the country to supply labor for agriculture and construction. Haitians here, desperate to escape the poverty and upheaval in their country, often say they have little choice but to accept Dominican exploitation.

Meanwhile, Dominican workers have been slowly pushed out of work by Haitian immigrants who will work for less, and so they are leaving their homeland in droves on rickety boats headed toward Puerto Rico, even though the Dominican Republic is one of the fastest growing economies in the Caribbean. Nationalist talk by the elite and frustration among unemployed Dominicans drive most attacks on Haitians, human rights groups say. And while one Dominican government after another has promised change, human rights investigators charge that they have all failed to guarantee Haitian immigrants and their Dominican-born descendants basic protections.

Guatapanal is not the only place where immigrants have experienced the Dominican Republic's version of mob justice. In August, on the outskirts of Santo Domingo, the capital, four Haitian men were gagged, doused with flammable liquids and set on fire. Three of the men, from 19 to 22 years old, died of their injuries. Soon after, Haiti temporarily recalled the leader of its diplomatic mission in the Dominican Republic to protest what it described as a "growing wave of racist violence" against its people.

After a Dominican woman was stabbed to death in May not far from here, Dominican mobs went on a rampage, beating Haitian migrants and setting fire to their houses. Before the next dawn, police officers and soldiers went door to door pulling some 2,000 Haitian migrants from their beds and loading them onto buses bound for the border.

At least 500 of those deported, Father Martínez said, were legal guest workers and Dominican citizens.

"It was a disaster," said Andrés Carlitos Benson, a Dominican-born university student who lives in Libertad. "We showed them our university identification cards, and they tore them up in front of us and told us to shut up, or they were going to beat us.

"They took parents away and left their children," he added. "They took old people out of their beds without any clothes."

Stung by mounting international criticism, President Leonel Fernández of the Dominican Republic has publicly expressed concern that some of his government's deportations of Haitians have violated international standards on human rights.

Still, his government rejected the ruling by the Inter-American Court. Other Dominican officials have said that their government was struggling with scant resources to secure its porous border and stop the surging flow of Haitians, which they blame for rising crime rates and overburdened schools, hospitals and housing.

A statement in late October by the Roman Catholic Bishops Conference of the Dominican Republic also said, "Our nation has a limited capacity to absorb excessive immigration," and pleaded for help.

"This is a very sensitive subject," said Ambassador Inocencio García, who is in charge of Dominican-Haitian relations at the Foreign Ministry. "I can tell you with all sincerity. We have institutional problems. We are making efforts to correct them. But in no way can the government of the Dominican Republic be characterized as one that does not respect basic rights."

Ambassador García said in an interview that a majority of poor Dominican children did not have birth certificates. But he did not respond to charges that Haitian children were routinely denied such documents.

The mayor here in Guatapanal, José Francisco Pérez, described the Haitians coming into this town as "an invasion." He said Guatapanal had 2,000 Haitians and only 500 Dominicans.

Area landowners stopped hiring Dominican workers for $10 a day because Haitians accepted less than half that, he said.

"Now instead of hiring 40 Dominican workers for a field, they hire 400 Haitians, and the Dominicans are left with nothing," Mr. Pérez said. "There's too many Haitians. If the government is not going to help us get rid of them, then we will do it ourselves."

Some landowners criticized the attacks by the Dominicans, and they have brought back many of the workers who fled.

"The problem is that there is no real justice," said Francisco Cabrera, who rents a few dozen acres of tobacco land here and uses Haitian laborers. He said the police rarely tried to stop attacks on them. "So people take justice into their own hands."

Polivio Pérez Colon, 36, one of the Dominican overseers who led the mobs against the Haitians, said they did not mean the immigrants any real harm. But he agreed that the Dominicans here felt outnumbered.

"They are people who do not use bathrooms," he said, referring to Haitians, many of whom live in shacks without running water and electricity. "They walk around drinking and making a lot of noise at night. Sometimes the men dance with each other.

"It's not that they are all bad. But they have to submit to our way of life. If not, these problems will keep happening."

No comments:

Post a Comment